The Dutch national museum in Amsterdam has launched a hard-hitting exhibition on the role of slavery in a period typically referred to as the Dutch Golden Age. In photo: Foot stocks designed for the constraint of multiple enslaved people, with six separate shackles, c.1600-1800. (Rijksmuseum photo)

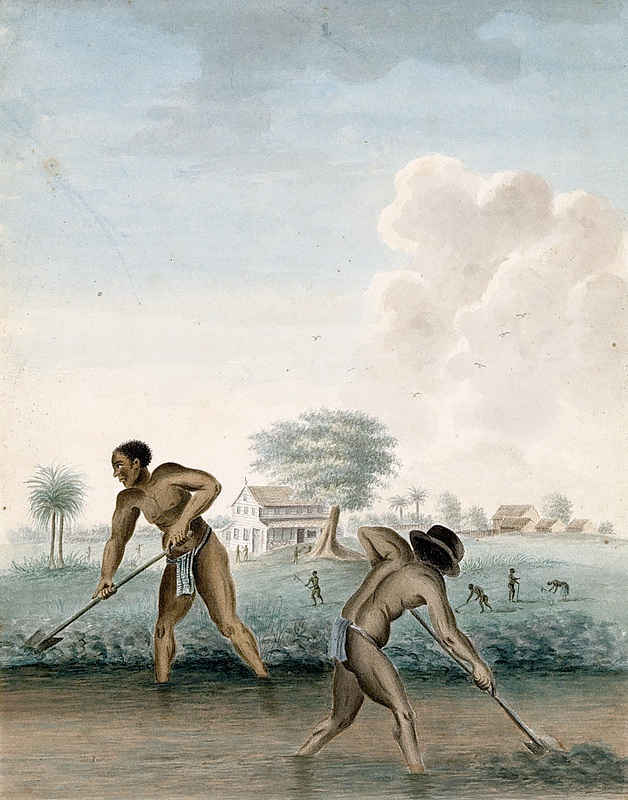

Enslaved men digging trenches around 1850. (Rijksmuseum photo)

King Willem-Alexander (right) opened the slavery exhibition at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

A scene at the event

AMSTERDAM--Telling ten individual stories to represent 250 years of “legalised injustice,” the Rijksmuseum, the Dutch national museum in Amsterdam, has launched a hard-hitting exhibition on the role of slavery in a period typically referred to as the Dutch Golden Age. The exhibit, which has been four years in the making, was ceremonially opened by King Willem-Alexander on Tuesday and runs until August 29.

Although extensive material is available online, it will only be physically open to Dutch schools from Wednesday, in line with COVID-19 restrictions.

“It is an exhibition that is not about numbers but about people: 10 lives that were part of the system of slavery,” said Rijksmuseum general director Taco Dibbits during a press conference. “We want as many people as possible to see the exhibition, to dwell together on what the past means for today’s society.”

“Slavery” includes 100 objects on loan from other museums, including modern artwork “La Bouche du Roi” (“The King’s Mouth”) by artist Romuald Hazoumè from Benin, which recreates a slave ship out of 304 jerrycans and bottles to represent its cargo of African men, women and children.

The 10 stories in the exhibition range from Wally, an enslaved man on the Palmeneribo sugar plantation in Suriname, who escaped in 1707 and was tortured, burned alive and decapitated, to Surapati, an enslaved Balinese man who became a national hero in Indonesia for battling the Dutch East India company and dying in conflict.

It also looks into “slave holders” and people who profited from the trade and exploitation of humans, such as Oopjen Coppit, a rich resident of Amsterdam who was painted by Rembrandt on the occasion of her wedding.

Her first husband, Marten, grew up in his father’s sugar refinery in Amsterdam, making a fortune from sugar produced by slave labour. Her second husband, Maerten Daey, had served as a soldier in Brazil under the Dutch West India Company regime. There, he also held captive and raped an African woman named Francisca who, according to church records, later gave birth to a daughter named Elunam.

‘Divisive’

Rijksmuseum history department head Valika Smeulders said the exhibition had an urgent role in showing how people can be, and still are, treated differently because of their religion or skin colour.

“For some in the Netherlands, it is a grey, far-away history, and for others it is history that is alive and they want to know more about it,” she said. ‘This is history that can be considered divisive, but it is also history that can be told to make connections.

“Colonial slavery is behind us and modern-day society has no responsibility for it anymore. But what we can take responsibility for is what we do with it. Understanding it better will give us a better understanding of where our society comes from and how we can shape our future.”

She said that by telling individual stories in all of their complexity, the museum wanted to make connections with all kinds of audiences.

“It was a tough task to make an exhibition that people could relate to about an unthinkable system from the past, where people were legally made into objects and where the state allowed people to be traded for generation after generation,” she said. “What would you, or I, have done in these circumstances?”

Sources

Another problem was the lack of conventional source material, because enslaved people – as they are called, rather than “slaves” – were not permitted to have possessions, many could not read or write, and few appear in paintings. This is why the exhibition includes objects including church records, legal documents, physical tools or weapons such as machetes and stocks, but also words from oral storytelling and songs.

Investigations included biological study; for example, to show the African origin of a type of rice that legend has it an enslaved woman called Sapali, in Suriname, hid in her hair when she escaped.

Parallel to the exhibition, the museum will also add labelling to objects and paintings in its fixed collection that have a link with slavery, after extensive new research aimed at telling a fuller story of the Netherlands’ history.

Eveline Sint Nicolaas, senior conservator in history at the Rijksmuseum, said the exhibition told 10 true stories from an unrecorded history of millions.

“Under Dutch authority, around 600,000 people were enslaved in Africa and taken over the ocean to the Americas,” she said. “Even more people were shipped to places around the Indian Ocean. For many of these people, we will never be able to tell their stories.”