By Robert Luckock

PHILIPSBURG--When one talks of reforestation projects, a country like Brazil might quickly come to mind, as the country aims to restore 12 million hectares of degraded land by 2030.

On a smaller scale, on another continent, Daniël Halman, a former Milton Peters College (MPC) student of Dutch nationality, born in St. Maarten, is currently engaged in a reforestation, agroforestry project in Senegal, West Africa, which is transforming the lives of farming communities and boosting their meagre incomes. The project, started in 2025, combines climate-controlled greenhouse technology with agroforestry.

The positive impact this is having on the communities has drawn approval from the Senegal government.

The project came about through a chance meeting in the Netherlands with Paula Medina Agromayor from Spain who had already spent time in Senegal and encouraged Daniël to visit the country. The pair have very different backgrounds but were united on their shared passion to make a difference in a part of the world that can be misunderstood.

Daniël, the son of retired former Orco Bank Manager Ronald Halman, studied architectural engineering at Delft University in the Netherlands obtaining his Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees, choosing a technical path focusing on climate design, how to cool and heat buildings, using sustainable materials instead of concrete and steel, how to make indoor climates comfortable without excessive electricity, and so forth. All of that study would come in very useful.

“I met Paula at a beach clean-up in the Netherlands during the first year of my Masters,” Daniël explained. “She persuaded me to come and take a look at Senegal. We also did a trip to East Africa to learn more about the culture and lifestyles on the continent. At that point during my Master’s thesis I decided to dedicate it to a project in Senegal. I found the culture of Senegal very interesting and similar to St. Maarten and we decided to settle. I feel very much at home there. The people are warm and hospitable.”

The pair are based in Kholpa, a small village of 1,500 inhabitants, close to Dakar. Senegal has around 12 recognised local languages representing different ethnic groups, but the official administrative language is French, which is also taught in schools.

“The one most widely spoken is Wolof, the lingua franca in Senegal,” Paula explained.

“Paula is almost fluent in Wolof,” interjected Daniel.

They remark about the diverse bird life, noted for their striking colours. The Zazu bird, a character from the “Lion King”, is often spotted in their village. Sadly, their and other animals’ habitat is threatened due to the very arid conditions and lack of trees.

Paula completed her last two years of high school in Singapore before earning a “Global Citizen Year” scholarship, a cultural linguistic integration programme for recently-graduated high school students. She spent her gap year in Senegal living in a small village with a local family. She attended seminars on politics, history and economics of Senegal and gave Spanish and English classes in the local high school in the village of Khombole.

“I was very motivated by Senegal, and have always been touched by the migration situation of Senegalese people living in Spain, living with no rights, having to do demeaning jobs because they couldn’t get legal jobs. It was very interesting to see the other side of the story in Senegal and meet people who could have been potential migrants.”

In the Netherlands, she completed a Bachelor’s degree in international studies with courses orientated towards politics and history of Africa, and for her Master’s she specialised in public administration, particularly on policy of migration diversity.

Returning to Senegal, she worked as Secretary General of the Spanish Chamber of Commerce and coordinated professional training and work insertion programmes for youth in Senegal which were connected to migration. It was financed by the Canary Islands government which wanted to find solutions for the youth to stay in Senegal.

“I was coordinating a programme on training sectors and trying to connect them with companies looking for people. But after a year and half, I decided I wanted to do something more in the field, something less political. That’s when I joined up with Daniël as project developer,”she said. “Daniël is more on the technical side with design and I am on the social side, making sure we have a positive impact, monitoring and evaluating projects, trying to find new partners and financing etc. Our skills are complementary but very different.”

Daniël created the company Féro (a word play on forest) for the greenhouse and agroforest projects and a company in the Netherlands to find funding for their projects in Senegal as well as a subsidiary company of Féro to do installation and construction work.

“We are a social enterprise. We work with small profit margins which we use for growing our business/impact,” he explains. Until now, because we are still a start-up, we have been working with grants as our sole income. We received a small grant from TU Delft University to start and also from the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) in the Netherlands, and the Dutch Enterprise Agency.”

Adds Paula: “The risk with non-governmental organisations (NGOs) is that when the time frame ends, there’s no more project management and funding, leaving the project abandoned. We see a lot of that in Senegal. The user feels it is not something they are co-creating, building. or involved in financially because it was just paid for and given to them.

“But we work for the private sector. Our focus is on helping small-holder farmers to thrive. We want them to feel it is also their investment. When we leave, the farmers will have the tools to carry on managing the system as if it was their own.”

Daniël says he was shocked to learn when doing his research that farmers earn only US $1,000 per year.

“I wanted to find solutions, by using methods we take for granted in the West, but that could work here. The farmer’s income is never going to be sufficient if they want to develop themselves further than where they are now. I realised the answer lies with greenhouses to create a micro climate for plants to thrive. I can already design indoor climates so I applied that to farming. Now I tell people I studied architecture to become a farmer,” he adds with a laugh.

The west side of the country is semi-arid, completely deforested for crop land. Peanuts, black-eyed peas, are the main crops farmed, including a hibiscus flower used for juices. The challenge for farmers is that the rainy season in Senegal lasts only three months for farming, with the rest of the year having dry, desert-like conditions.

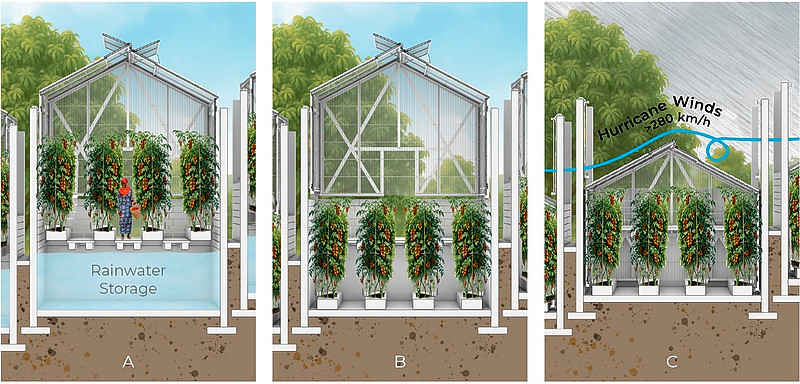

Greenhouses however, allow farming for 12 months of the year. They include a rainwater collection system that permits water to be used in the dry season, covering 50-60% of the irrigation demand, and reducing pressure on groundwater wells.

“The model that we came up with includes a 400m2 greenhouse built with bamboo with one hectare of land. But that greenhouse can produce between 6,000 to 12,000 euros per year in value of produce (three to nine tons), a significant increase in the farmer’s income.

“Over 10 years, when they get better and better, their income can increase up to 18 times what they were farming before. And that’s only using 2% of the land they own. The greenhouse is always sold to them with an agroforest which is an incentive to reforest their land, because it’s profitable. Our slogan is ‘Reforestation our way is too profitable to ignore’.”

The selling price for the greenhouses has not yet been finalised. Due to investment in plastic cover material production in Senegal using recycled bottles instead of imported plastic from Europe, the price is expected to come down. The agroforest costs vary depending on size. Together the two investments can bring the farmer’s income to more than US $20,000 per year.

With the technology making economic sense, Daniël and Paula want to apply it to address the migrant situation in Senegal, to create opportunities for potential migrants. They also want to bring the project to St. Maarten.

A hurricane-resistant prototype greenhouse, seven metres high, has been built in steel. The design includes a reinforced steel mesh that covers and transforms the greenhouse into a pyramid shape, thereby reducing the wind load by 60%. Daniel said the government in St. Maarten was “very receptive” to the idea when it was pitched to them.

“It’s been four years since we were in St. Maarten and we were shocked to see the price of vegetables. It’s high time we start producing our own vegetables. In the future we want to put our creativity, ingenuity and skills to the test, not only in Senegal and St. Maarten, but in the agriculture sector of other countries to find solutions for them.”

The pair will open another subsidiary in St. Maarten in 2026, to develop the greenhouses. For St. Maarten they will work with Intersystems, another local company, to build the greenhouses.