PALMIRA, Colombia--For nearly a year the ex-rebels worked shoulder to shoulder with their former enemies - retired soldiers from the Colombian military - in a place that viscerally expresses the toll of Colombia's six decades of conflict: a cemetery.

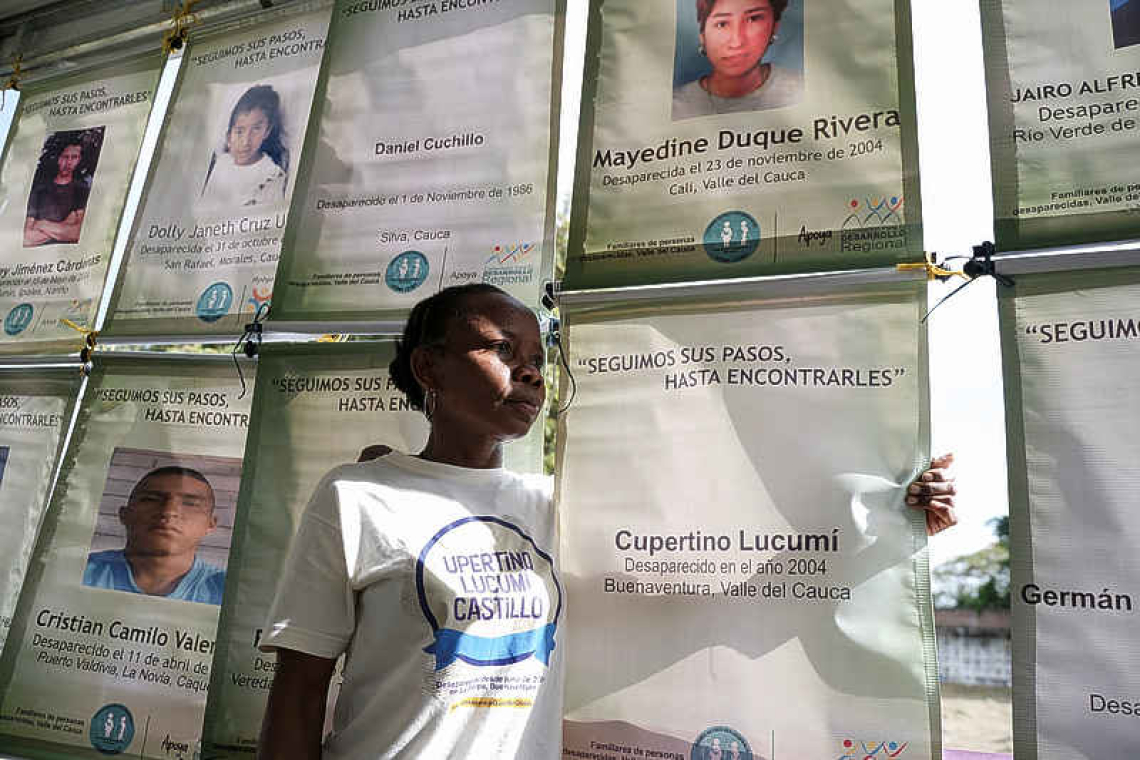

The former combatants helped exhume unidentified remains believed to belong to conflict victims and then refurbished this corner of the cemetery in Palmira, in western Colombia, building new ossuaries and a tiny chapel. The project - the first of its kind - is a reparation effort taking place under the terms of the 2016 peace deal which led to the demobilization of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) rebels and set up a transitional justice court to try former guerrillas and military members for war crimes. At least 450,000 people are known to have been killed in Colombia's long civil war. A further 132,877 people are recorded as disappeared - their whereabouts unknown. The vast majority are likely dead.

The ex-combatants taking part in this project were largely mid-level commanders, and their work will be taken into consideration by the transitional justice court when eventual reparations sentences are handed out. The process forced the ex-combatants to see their erstwhile adversaries as human beings, they told Reuters, and also to engage with conflict victims. "We're human beings. They took one side and we took the other, theirs an illegal one and ours a legal one.

And in the end we all found ourselves on the same path," said retired army sergeant Fabian Durango, who spent 16 years in the military after joining in 1998. "We're here to try and mitigate the evil we did," said Durango, a veteran of special forces and counter-insurgency units who spent months in the deep jungle. Durango, who was 15 when he joined the army, is facing charges in the court's probe into so-called "false positives," when soldiers murdered civilians and reported them as guerrillas killed in combat to receive benefits. "In that moment you thought of yourself more than anything," said Durango, who admits the crimes. "It's a harm that whatever you do or don't do, you'll never repay."

"The pain of their mothers has no reparation," he said. A former FARC commander who uses the nom de guerre Leonel Paez and declined to give his real name because he feared threats from former comrades said the Palmira project showed understanding is possible. "We became friends, and we didn't look at each other differently because you were a soldier or a rebel," he said.

"Destiny put us against each other." Paez joined the FARC in 1979, when he was 17, and is accused of participating in kidnappings for ransom and of crimes committed in the region around Palmira. He says he may also face charges over child recruitment. The remains of unidentified bodies exhumed from the area of the cemetery known by locals as "the forgotten corner" will have DNA samples taken and compared to a database of families of the disappeared.

If identified, their families can choose where to give their loved ones a final, proper burial. Some victims' groups have painted a mural and planted a flower garden around the restored area. Judith Casallas is happy the resting place is now more dignified. Her 19-year-old daughter Mary Johanna Lopez disappeared with boyfriend Jose Didier Duque in 2007 in the nearby town of Pance, where the couple had gone in search of a cabin to rent for his birthday.

No trace of them has ever been found. Casallas' participation in the project put her in contact with ex-combatants who were active when her daughter, the youngest of three girls and a voracious reader, vanished. "It was useful to communicate to them where my daughter disappeared. There were a lot of people here from that time, both army and (FARC) signatories," Casallas said, adding that some ex-combatants told her they would ask around about her case.

Casallas, who suffers from heart and kidney problems, still buys a Christmas present for Mary Johanna every year. She has 18 saved up. She urged ex-combatants to tell the truth about their crimes to potentially help find the remains of the disappeared. "The day that I get my daughter's remains, I will believe she's gone," said Casallas.